Mental State Matters More Than Technique

- community0385

- Jan 21

- 5 min read

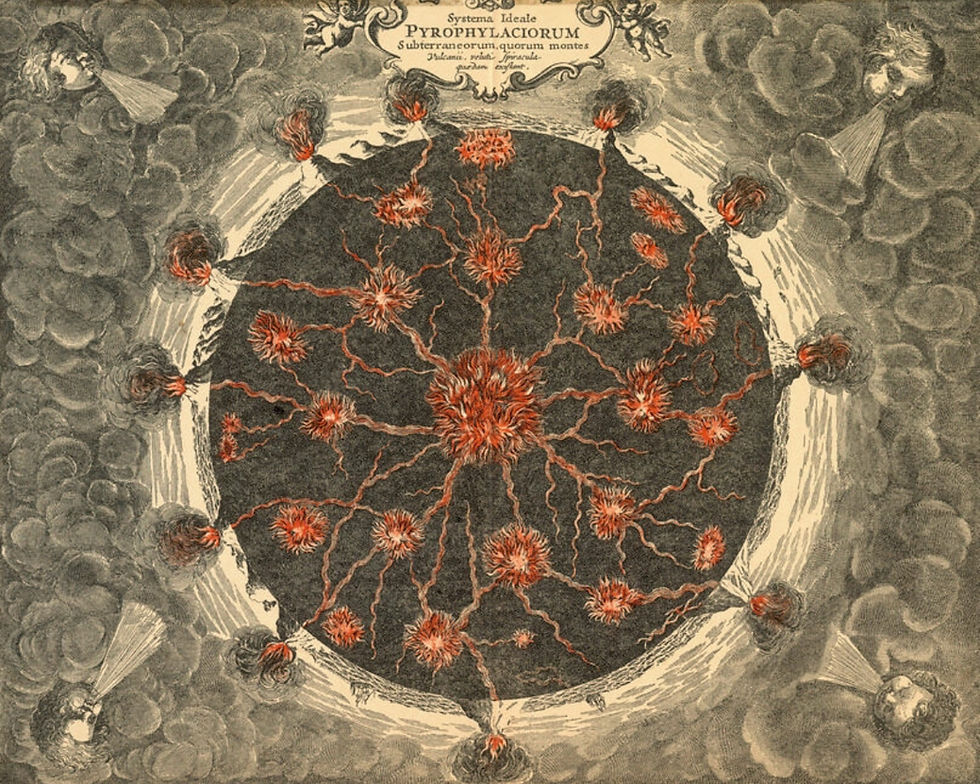

Picture: Egyptian wall painting from the tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hasa, 12th Dynasty, around 1920-1900 BC.

We tend to believe that mastery in life whether in work, creativity, relationships or adversity is primarily a technical problem. The cycle goes like this - learn the skills - optimise the process - refine the method. Yet across domains such as performance psychology, trauma research, contemplative practice and even psychedelic science a different pattern emerges - mental state determines what techniques are even available to us in the first place. Technique does not operate in a vacuum - it operates inside a state of consciousness. When that state shifts, the same skills can either function or dissolve and disappear. This becomes especially clear under pressure. Research on performance consistently shows that people rarely fail because they lack ability - they fail because self-consciousness overwhelms execution. The problem is not insufficient competence but excessive self-reference. The mind tightens around the question of ‘me’ and action becomes constrained by narration, judgment and anticipation (Beilock & Carr, 2001).

One of the most misunderstood psychological mechanisms involved here is dissociation. Dissociation is often treated as inherently pathological but clinical psychology describes it as a spectrum. At one end are everyday experiences like absorption, daydreaming and ‘losing oneself’ in a task and at the other are severe dissociative disorders associated with trauma. Between these extremes lies a wide range of non-pathological dissociative states that serve adaptive functions, particularly under stress (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Moderate dissociation reduces emotional reactivity, dampens self-referential thinking, narrows attention and allows action to proceed without constant narrative interference. In this sense dissociation is a reorganisation of it. The autobiographical self steps back and task-oriented processing comes forward. Fear diminishes because the self that fears becomes less dominant. Fear diminishes not because it is suppressed or overcome through force of will but because the centre of experience shifts. As dissociation increases in its moderate functional form the autobiographical self that anticipates, evaluates and fears weakens allowing action to proceed without being filtered through personal threat. In this sense fear is inversely related to dissociation - when identification with the self is tight, fear dominates - when identification softens fear naturally recedes. Stanislavski described this same mechanism in practical terms. He observed that fear on stage arises when the actor becomes self-conscious which is aware of themselves as an object being judged rather than absorbed in the given circumstances of the role. When attention moves away from the personal ‘I’ into purposeful action fear dissolves without being addressed directly. The actor does not eliminate fear by trying to feel brave but by allowing the self that fears to step aside so that psychophysical action can emerge. In both cases, fear fades not through control but through a redistribution of where the self is located in experience.

This mechanism overlaps strongly with what has been described as flow. Flow states are characterised as a loss of self-consciousness, altered time perception and a sense that action is unfolding spontaneously. Neurocognitive models suggest that flow involves transient reductions in activity within brain regions responsible for self-monitoring and executive self-regulation, allowing well-learned skills to run with minimal interference (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Dietrich, 2004). Subjectively people describe flow as a disappearance of the inner narrator - there is doing but no one commenting on the doing. Similar to meditation or ritual.

From a Jungian perspective this can be understood as a temporary withdrawal of the ego rather than its destruction. Jung viewed the ego as a necessary centre of identity but not the totality of the psyche. When the ego clings too tightly to control it becomes rigid and fragile. Encounters with intensity, uncertainty or the unknown often dissolve ego boundaries exposing individuals to what Jung called the numinous - experiences that overwhelm ordinary self-concepts and reorganise meaning (Jung, 1959). In such moments action can emerge from deeper, less personal layers of the psyche. However, identifying with these states rather than integrating them leads to inflation and imbalance.

Modern psychedelic research provides a biological correlate to these observations. Studies using neuroimaging consistently show that substances like psilocybin and LSD reduce activity and connectivity in the default mode network, a brain system strongly associated with self-referential thinking, autobiographical memory and identity maintenance. This states reduction corresponds to experiences of ego dissolution, increased present-moment awareness and reduced fear of self-loss (Carhart-Harris et al., 2012; Carhart-Harris et al., 2014). Similar patterns of reduced default mode network dominance have been observed in experienced meditators and during flow states suggesting a shared mechanism across very different paths to altered consciousness.

When self-referential processing loosens, perception reorganises - attention becomes more immediate, less evaluative and less burdened by identity which can feel liberating and meaningful but it can also be destabilising if pursued without context or integration. This reframes how we understand mental resilience. Resilience is often described as toughness - pushing through fear, suppressing doubt, forcing confidence. But the evidence points in a different direction - resilience emerges from flexibility rather than rigidity, from the ability to modulate identification with thoughts and emotions rather than dominate them. Dissociation when moderate and reversible is one way the psyche creates that flexibility. It allows distance without disconnection, action without self-attack and presence without overwhelm. The danger arises when dissociation becomes the only reliable regulator of experience. When ordinary states of consciousness feel intolerable, when identity fuses with extreme clarity or intensity, when returning to baseline feels like loss, dissociation shifts from a tool to a dependency. This is why practices that reduce self-reference must be paired with integration. The goal is not permanent ego dissolution, emotional numbness or transcendence but the ability to move fluidly between states without becoming trapped in any one of them.

These dynamics are not limited to extreme contexts, they appear wherever identity feels threatened - creative work, leadership, public expression, conflict, grief and change. In all of these areas technique matters but mental state governs access. A regulated, spacious state allows skills to express themselves naturally and an over-identified ego constrains them. Mental state matters more than technique because it defines the field in which technique operates - true mental resilience is not the absence of fear nor the conquest of the self but freedom from being ruled by the self when it tightens in response to threat. It is the capacity to step back when needed and that flexibility is what allows us to meet life with precision and resilience.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Beilock, S. L., & Carr, T. H. (2001). On the fragility of skilled performance: What governs choking under pressure? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(4), 701–725. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.130.4.701

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Erritzoe, D., Williams, T., Stone, J. M., Reed, L. J., Colasanti, A., Tyacke, R. J., Leech, R., Malizia, A. L., Murphy, K., Hobden, P., Evans, J., Wise, R. G., & Nutt, D. J. (2012). Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(6), 2138–2143. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1119598109

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Leech, R., Hellyer, P. J., Shanahan, M., Feilding, A., Tagliazucchi, E., Chialvo, D. R., & Nutt, D. J. (2014). The entropic brain: A theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, Article 20. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00020

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row.

Dietrich, A. (2004). Neurocognitive mechanisms underlying the experience of flow.

Consciousness and Cognition, 13(4), 746–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2004.07.002

Jung, C. G. (1959). The archetypes and the collective unconscious (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton University Press.

Comments